While solar eclipses were well understood in antiquity and correct diagrams of eclipses were made from the time of Claudius Ptolemy and earlier, it was not until the Age of Enlightenment when the earliest maps of the actual path of an eclipse on earth appeared.

The emergence of eclipse maps represents the convergence of several advances in scientific thought -- the heliocentric model developed by Nicolaus Copernicus, Johann Kepler’s laws of planetary motions developed from Tycho Brahe’s measurements, and new geographic knowledge spanning the old and the new world with a system of longitude and latitude values.

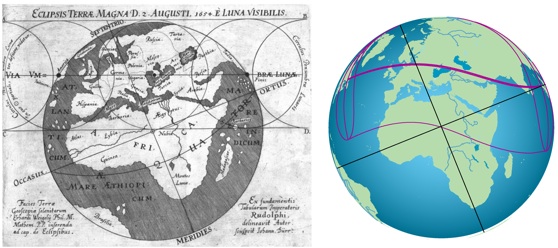

The earliest known map of a solar eclipse

The earliest known solar eclipse map was created in 1654 as part of an academic disputation involving Erhard Weigel, professor, and Andreas Gunther Seiffart, student, on the subject of the astronomical theory of eclipses. (An academic disputation is a formal system of debate to establish the truth of a theory based on accepted sources and logic). The map was engraved by Johann Dürr. The calculations made by Weigel and Seiffert were based on the Rudolphine Tables of orbital elements calculated by Kepler.

Erhard Weigel (1625-1699) was a German mathematician and astronomer in Jena (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Erhard_weigel) and played an important role as an advocate for calendar reform in Germany. He also instructed Gottfried Wilhelm Liebniz, one of the inventors of the calculus, at Jena University.

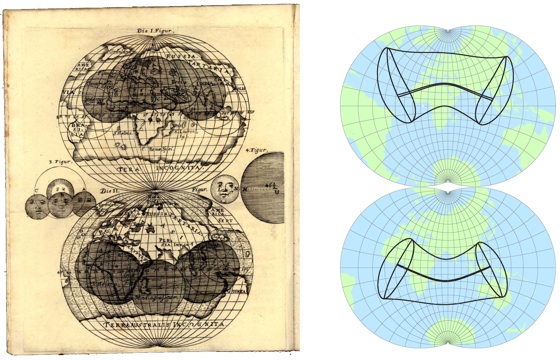

Another early eclipse map from Germany

In 1676, Johann Christoph Sturm (1635-1703), professor of astronomy, mathematics, and physics at Altdorf University, published an 34-page almanac called the Finsternissen-Kalendar.

In a similar fashion to the first eclipse map by Erhard Weigel, the eclipse is depicted as a series of circles representing the penumbral shadow of the moon, but this map more accurately maps the eclipse as a curved path of eclipse instead of a straight line.

Eclipse maps by Cassini

Another early innovator of early eclipse maps was Giovanni-Dominico Cassini (1625-1712). Cassini seems to have constructed an eclipse map in the 1660’s but this map has not been found.

In 1700, Cassini published a retrospective map of the eclipse of 1699 September 23. This was the most accurate eclipse map up to this date and begins to resemble modern eclipse maps.

An important feature of this map is the introduction of isomagnitudes (lines of equal maximum eclipse) in solar eclipse maps. In this era, the obscuration of the sun by the moon during an eclipse was measured in parts of 12 and called digits (doigts in French). This map contains curves labelled “6 doigts”, or 6/12th maximum eclipse, “5 doigts”, or 5/12th maximum eclipse, and “12 doigts”, the path of the total solar eclipse.

This convention of dividing the maximum eclipse into intervals of twelve “digits” began in antiquity and endured well into the 19th century and appears in maps from Germany, England, France, the Netherlands, Czech Republic, and the United States. The last examples I can find are in the American 1844 map by Williams and the German 1846 map by Heck.

Today, isomagnitudes on eclipse maps are expressed in decimal intervals, typically 10% or 20%, sometimes even 1%. This might be related to the trend towards the widespread (except in the United States) adoption of the metric system in the 19th century.